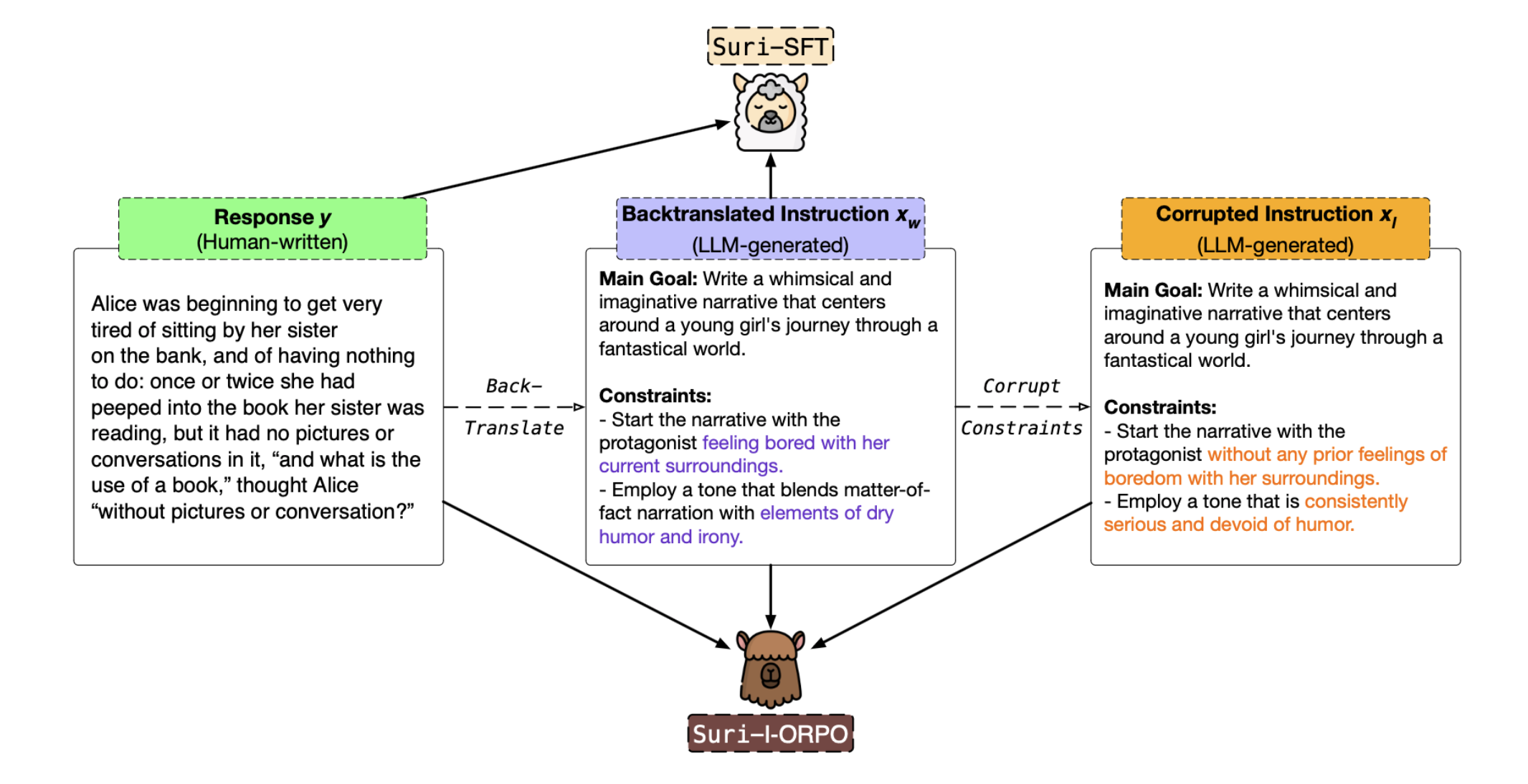

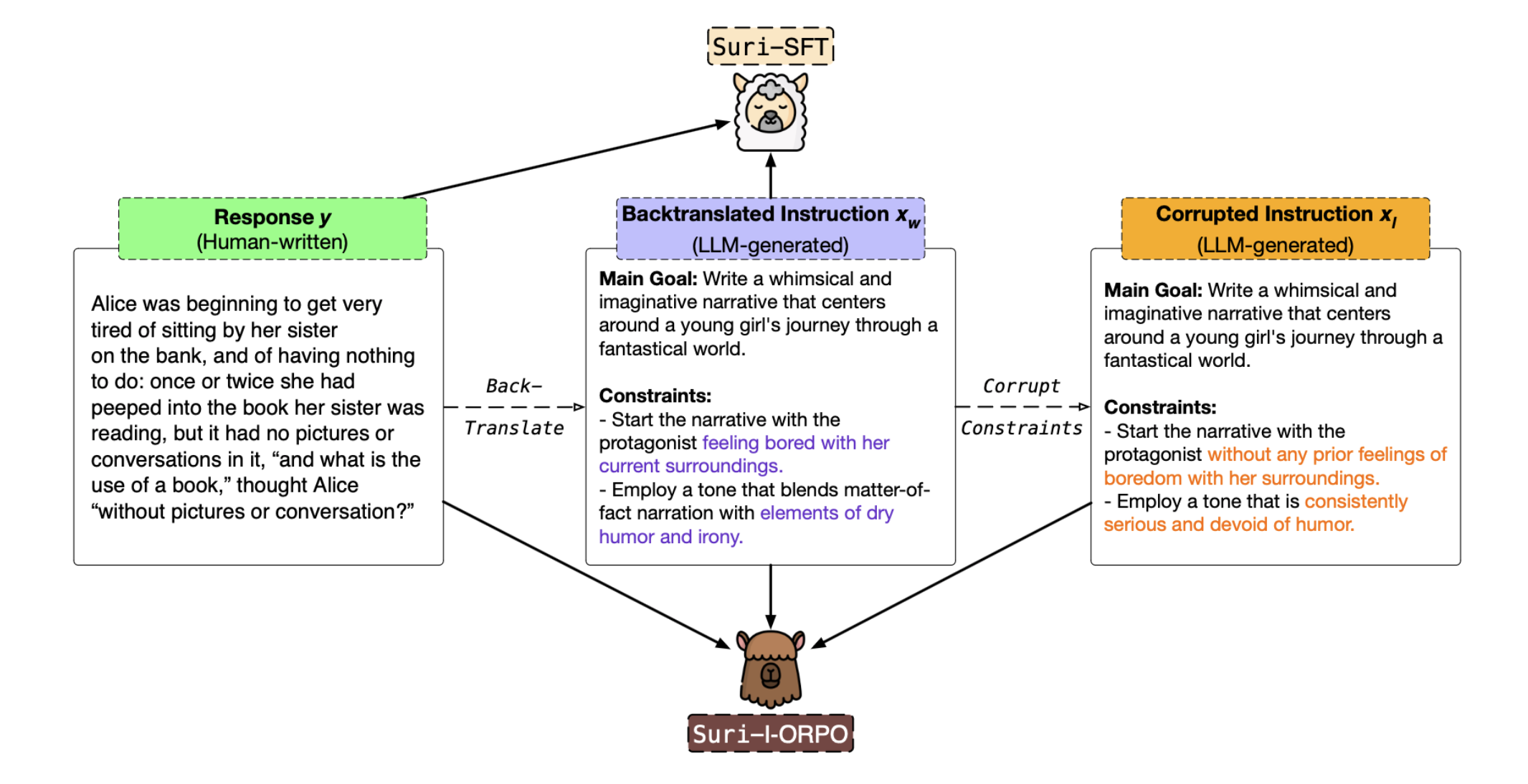

1. We introduce a new dataset, Suri, which contains multi-constraint instructions (~10 constraints per instruction) and lengthy gold responses (between 2k and 5k words).

2. We propose I-ORPO, a variant of ORPO (Hong et al., 2024) that handles chosen and rejected prompts rather than chosen and rejected responses.

where

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}_{\text{I-OR}} = - \log \sigma \left(\log \frac{\textbf{odds}_{\theta}(y|x_w)}{\textbf{odds}_{\theta}(y|x_l)} \right) \\ \textbf{odds}_{\theta}(y|x) = \frac{P_{\theta}(y|x)}{1- P_{\theta}(y|x)} \end{align} $$3. We find that fine-tuning Mistral-7B-Instruct with I-ORPO and SFT results in significantly longer generations and decent constraint-following ability. In addition, SURI-I-ORPO generations are generally preferred for their coherent and informative incorporation of the given constraints.

4. We observe that GPT-4o does not reliably evaluate the constraint-following ability of long-form text generations.

Access the full dataset here: Suri. To also access the Books3 subset, please refer to our Github repository for detailed instructions.

Instruction

Compose a detailed and engaging lecture on the development of architecture from the late Middle Ages through the early Tudor period, focusing on how socioeconomic changes influenced architectural styles and practices, the rise of a new consumer class, and the evolution of residential, religious, and commercial buildings in England. - Begin the lecture with a recap of previous discussions, emphasizing the impact of economic crisis and demographic changes on architecture, and express an intention to balance previous focuses by shifting attention to the living conditions of ordinary people during the period. - Introduce the Black Death and agricultural recession as pivotal events that led to significant changes in the countryside, including depopulation and its surprising benefits for the survivors in terms of improved living standards and economic opportunities. - Detail the reversal of land management trends among landlords around 1380-1410, highlighting the shift towards renting lands for a guaranteed income and the emergence of a new class of tenant farmers who significantly influenced social and architectural landscapes. - Describe the architectural characteristics of timber-framed farmhouses built by this new class, noting regional variations and specific examples that have survived to the present day. - Explain how these socioeconomic changes extended to affect the design and function of the houses of the rich, emphasizing decreased household mobility, the need for more storage, and the consequent rise in local consumption of goods. - Discuss the construction of towers and gatehouses by the aristocracy as symbols of status, including specific examples and how these structures evolved to become more integrated with residential spaces. - Address the development of commercial architecture, particularly inns, taverns, and alehouses, and how these establishments catered to different aspects of social life and commerce, including the architectural distinctions among them. - Transition to church architecture, noting how royal patronage from the late 15th to early 16th centuries led to significant ecclesiastical constructions, and describe the stylistic changes and specific examples of royal commissions. - Discuss the impact of economic conditions on monastic architecture, detailing how the quest for individual comfort and privacy among monks and abbots led to architectural innovations within monastic communities. - Introduce brick as a significant architectural material in the 15th century, explaining its advantages, the introduction of manufacturing improvements from northern Europe, and its impact on the aesthetics and construction of buildings. - Conclude with a reflection on the broader social and cultural shifts of the 15th century, including the rise of a more mobile and less stratified society, and hint at the dramatic changes to come with the Reformation, setting the stage for future lectures. - Throughout the lecture, maintain an engaging and informative tone, incorporating anecdotes and specific details to illustrate points, and encourage listeners to explore these architectural examples firsthand.

Gold Response

How the Middle Ages were Built: Coming of Age, 1408-1530 In my last lecture we took a look at a century that was dominated by economic crisis and demographic collapse. I described how out of this turmoil came a distinctive architectural style often described as the perpendicular style. In doing so we mainly concentrated on polite architecture, on castles, churches and palaces. I want to start tonight by righting that balance as we have not heard, for a while, about where more ordinary people lived. The Black Death and agricultural recession had a huge impact on the countryside. Between 1370 and 1520 as many as 2,000 villages were abandoned and many more shrank in size leading to the abandonment of half a million buildings. Yet this drastic depopulation of the countryside was, surprisingly, largely to the advantage of the people who lived there. Because there were fewer people basic foodstuffs were cheaper and more meat and fish was available: as a result people’s diet markedly improved. Wages were also higher, unemployment was lower, the choice of jobs was wider and women took on skilled jobs like weaving. But the real change was the opportunity presented by landowners. Three lectures ago I described how between 1184 and 1215 landlords had moved to take their own lands into direct management but between 1380 and 1410 this process was reversed. Landlords realised that agriculture was now unpredictable and brought low profits and that in contrast renting their land would bring a guaranteed income. This change had a profound effect from around 1400 bringing a new and powerful group of farmers to prominence. A farmer is technically-speaking someone who pays a fixed rent or farm for their land and this new group of tenants acquired perhaps as much as a quarter of all agricultural land in England. Some were former employees of the lords, many were the richer peasants. This was a redistribution of wealth away from the aristocracy to a new class of people who created new social relationships and methods of production. Across large parts of England these men built themselves houses. Hundreds of timber framed farmhouses from the period 1430 to 1530 survive today in the richer parts of the country, in Kent and Sussex as far west as Hampshire and north into Essex and southern East Anglia. They share a broadly similar plan with a central hall open to the roof with two-story blocks at each end containing chambers. The whole was contained under a single roof and in some parts the upper floors were jettied out over the lower ones. Watermill House, Benenden, Kent, for instance, is still much as its late fifteenth century builder left it. In the midlands and western England similar types of building are found, although generally of a slightly humbler nature. What is really important about these houses is that they were detached from their farm buildings in such a way that there was nothing inherent in their design that revealed that they were lived in by farmers. These families had their own halls, just like their social and economic superiors, they had their separate bedroom, parlour and kitchen; some even had a screens passage. Beams were carved, doors panelled and windows filled with glass. Decorative metalwork, drains and gardrobes were all now commonplace. The owners of these buildings were active consumers of a wide range of household goods. Decorative ceramics, in particular, would have been ubiquitous, but furnishing textiles and furniture were also in great demand. To the English countryside was now added a type of housing below that of the gentry and above that of the peasant house, well built and tuned to the lives and aspirations of a new consumer class. The same processes that created the farmers and their farmhouses had an impact on the lives and the houses of the rich. The most important development for them from around 1300 was a noticeable decrease in household mobility. Early medieval households were always on the move but during the fourteenth century noble households moved about less, some stayed put for most of the year. This had no single cause, but the fact that so much land was now tenanted to farmers meant that lords could not live off their own estates as they travelled around and at the same time had less reason to visit their far flung holdings. Much longer periods spent in one place affected the design and economy of the great houses. For instance much more storage space was needed for household goods and provisions, for wine in cellars and for textiles in wardrobes. Permanent staff had to be accommodated in ranges of lodgings and these people had to be provisioned all the year round. Great houses became huge local consumers of firewood, candles and foodstuffs stimulating local markets in a way they had not done before. Thus, as I described in my last lecture, great houses became larger, more complex, and more richly appointed and most lords chose one, or at most two houses that could be brought up to the expected standards. Most landlords saw their income reduce during the fifteenth century but the long period of decline slowed down in around 1470 and from then until the 1520s most saw an increase in revenue. This led to an upswing in aristocratic building. Towers, either free-standing or as gatehouses, had been at the core of English aristocratic building from late Saxon times and they never became unfashionable, they were a dominating presence, expensive to build, conferring status on a place as well as being agreeable places to live with great views. During the late fourteenth century a small group of aristocrats built a new sort of tower which was, in effect, a complete residence integrating hall, chapel, lodgings and domestic offices. The best of these were at Warkworth Castle, Northumberland, dating from 1377 and Old Wardour Castle, Wiltshire started in 1393. These were precursors to the huge integrated tower started by Henry V and designed by the King’s mason, Stephen Lote at Shene (modern Richmond upon Thames) in 1414. It was almost certainly this spectacular new royal palace at Shene, nearing completion in the 1430s, which re-energised the constructionof great towers in a number of new aristocratic mansions. The men who built these were close to the royal family: Ralph, Lord Cromwell, Treasurer of England, built Tattershall in Lincolnshire in 1434-46; the most powerful man in Wales, William Herbert, earl of Pembroke built at Raglan Castle, Gwent from 1461 and William Lord, Hastings Edward IV’s Chamberlain constructed a tower at Ashby de la Zouche in Leicestershire in 1474-83. Lesser men too followed with towers at their houses such as Lord Lovell at Minster Lovell and Sir Robert Harcourt at Stanton Harcourt, both in Oxfordshire. By the end of the fifteenth century these towers became less independent structures and more integrated with the principal lodgings of the house. Two buildings are particularly in this process. The first is Edward IV’s new lodgings at Nottingham Castle. There the king commissioned a massive new tower integrated with a fine range of lodgings. The lodgings were built against the outer curtain wall but they faced inwards with a series of seven two-story bay windows to the inner court. The king’s private rooms were positioned in the tower, but approached by three magnificent chambers of state. This was a radically new and important building. Here you see for the first time the use of bay windows as a decorative feature, a feature that was to go on and define Tudor architecture for a century or more. Then at Greenwich, in about 1500, Henry VII’s master mason Robert Vertue took this to the next stage. The royal palace there was not fortified in any way; it presented a long range to the river Thames with bay windows looking out both ways. In the middle, as part of the main range, a tower rose containing the king’s privy rooms. Greenwich was to become a blue print for houses of status and pretension for the following twenty years. In the autumn when I come on to speak of the great houses of the Tudor period, it is back to Greenwich that I will refer. This was a seminal building in the history of English domestic architecture. But the riverfront at Greenwich was only one range of a palace with two large courtyards. For houses of the first order a single courtyard would not suffice. Most large castles were planned on the basis of two courtyards, wards or baileys; an outer one for the household, retainers and services and an inner one for the lord’s family. In the late fourteenth century the largest courtyard houses adopted a second courtyard (or even a third) for exactly the same reason. Thus a very large country house like Dartington Hall or a big urban palace like the Archbishop of Canterbury’s at Lambeth, London would have two courtyards. The most impressive survival of this type is Wingfield Manor, Derbyshire (1440-1456) which can be seen as the precursor to the next generation of top-end aristocratic houses, the Duke of Buckingham’s Thornbury Castle, Bristol (c.1510-21), and Thomas, Cardinal Wolsey’s Hampton Court (1514-28). In most of these double courtyard houses the great hall was sited in the range between the two courts acting as the vestibule to the more private inner courtyard and the lord’s own lodgings beyond it. Now changing lifestyles of the aristocracy had wide ranging impacts. One of these was that as they travelled they now no longer stayed at their own houses – having now so few and relied much more on renting accommodation for the night. From early times people had rented out space in their houses for travellers, but by the thirteenth century Inns became common in most towns of any size. Inns were like hotels. Taverns, which provided good quality food and drink, including wine, were more like restaurants. Alehouses were pubs providing basic food, ale and on occasion rooms. From the sixteenth century these distinctions were recognised in law and defined licensing restrictions and the obligations of landlords. From a census taken in 1577 we can calculate that there were then around 17,367 alehouses, 1,991 Inns and 401 taverns in England. Alehouses were often just people’s ordinary residences, although larger houses with cellars were more successful venues. This is because before the 1450s when more alcoholic beer, fermented with hops, became common, ale which contained only malt yeast and water, needed to be kept cool if it was to last. The larger houses too would have had attached brew houses where ale, and later beer, was made. Taverns were also essentially houses, although larger and normally with cellarage for the storage of wine. Before the sixteenth century it was only the Inn that had a distinctive architectural expression. Inns were commercial ventures constructed by landowners, often monasteries to make money. The powerfully atmospheric George Inn, Norton St. Philip, Somerset, was built in the late fourteenth century by the Carthusian Priory of Hinton in order to provide accommodation for merchants visiting the market and more generally to stimulate trade. It is typical of a type of inn that presents a fine stone façade to the street with a hall, kitchen and rooms in a single range. A narrow archway led to the rear where, perhaps, there were stables. Similar, but later (c.1480) is the pretentious George Inn Glastonbury, Somerset, with a fashionable stone façade bearing the arms of the abbot who built it and those of Edward IV. The New Inn, Gloucester, is undoubtedly the most spectacular surviving example, but of a second type. Built by the Abbey in 1450 it is a three stories timber-famed building built around a central courtyard. On the street front there are shops and a passageway between them leads to the central court surrounded by upper floor galleries. These led to over twenty rooms. These were large, 20ft by 12-15ft and would have contained several beds for up to half a dozen occupants so the whole inn could accommodate perhaps 200 when full. There was a hall and kitchen and as series of parlours for private dining. The New Inn could accommodate the travelling household of an aristocrat with ease. The most important guests would dine in their own rooms which were furnished with tables chairs and benches. The less well off dined in the hall and shared beds with other travellers and a variety of bed bugs. A bed in a cheap inn would cost a penny a night, less than the cost of dinner; the swankier establishments, such as the George at Glastonbury would be more. But let me move on from the lives and houses of the aristocracy and turn now to the church. In my last lecture I explained that church building in the fifteenth century was not generally driven by the aristocracy or churchmen. I showed you churches such as this one in Saffron Walden which were the products of merchants and squires. I also explained that most parish church building was about extension and adaptation not complete rebuilding. There was, however a big exception to these points: one that I now need to address. For between 1415 and 1530 English Kings again became amongst the greatest patrons of church architecture in Europe. Henry V planned three monasteries next to his royal palace at Shene and completed a large Charterhouse there, Henry VI founded chapels at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge; Edward IV started a chapel at Windsor and a friary at Greenwich and Henry VII commissioned a lady chapel at Westminster and a friary at Richmond; most of these works only came to completion under Henry VIII. The royal monasteries are no more, but at Windsor, Westminster and Cambridge three remarkable buildings remain. They represent between them the stylistic changes that began towards the end of the fifteenth century, a process of increased richness or busyness of ornament and decoration. For those of you who have followed my lectures this should be no surprise. For every style of architecture that I have mentioned which started plain and restrained became, in due course elaborated and decorated. This is, in fact, a characteristic of English architecture, and we see it very clearly in the great royal commissions around 1500. In 1471 Edward IV commissioned a new chapel of St. George at Windsor Castle. This was to be an even more splendid setting for the services of the Order of the Garter in which the king took a special interest, but it was also to glorify the Yorkist line and provide a mausoleum and chantry for the Edward himself. The architect was Henry Janyns who had worked at Eton College for Henry VI Many of the elements of its remarkable interior will be familiar from Gloucester Abbey choir and Canterbury Cathedral nave both of which we looked at in my previous lecture, but the combination creates quite a different effect, not at all vertical, in fact the nave seems wider than it is tall. This is because the extensive use of four-centred arches (which have arcs of very low pitch) make the ceiling more like a cove than a vault. These arches became increasingly popular from around 1400 and almost ubiquitous after 1500 creating wide openings allowing in lots of light. St. George’s was finished in the reigns of Henry VII and VIII by which time another royal commission, conceived in a spirit of rivalry with Windsor, had been started. Henry VII commissioned a new Lady Chapel for Westminster Abbey which was to triple as a shrine to his pious uncle Henry VI and a chantry for himself and his family. This was the most ostentatious addition to the abbey since Henry III and was the triumphal statement of a nouveau riche king striving to be more lavish in every way than the chapel at Windsor. So rather than blank arcading between the arcade and the clerestory as at St. George’s, and elsewhere there is a band of niches each containing wonderfully expressive and lifelike statues. In the middle of the chapel was to be Henry VII’s chantry behind a gilt-bronze screen containing a monument to the king and queen, an altar and reredos with gold-covered figures, all topped by one hundred nine-foot long burning tapers. Above this rides the fantastical fan vault with stalactite-like pendants falling from the conical fans. The weight of this is taken by external piers fashioned as octagonal turrets crowned by ogee domes. But these are not recognisable as piers as they share the same grid of tracery as a series of tall bay windows squeezed between them creating a continuous cage of tracery round the lower part of the chapel. King’s College, Cambridge, had been begun by Henry VI in 1448 but in 1499 was still less than half completed. The finishing touches were only finally installed in the 1540s under the patronage of Henry VIII. The chapel combines more brilliantly than any other building the principles of design begun at Gloucester in the 1340s and 50s. The vaults, windows and panelling are perfectly integrated into a single cage of tracery, yet the detail is not what you see, for it combines to create a truly monumental space. The walls seem to be entirely of glass and the vault seems to confound gravity. Externally it is clear how this illusion was achieved as the elevation is broken up by the rhythmic verticality of massive buttresses. But even these are concealed by a low-level chapels which hide the full depth of the buttresses at ground level. While no English monastery built anything like the crown, we should not forget that the monasteries were still amongst some of the most important patrons of architecture. The monasteries did not escape the economic crisis coomon to landlords after the Black Death. During the first half of the fifteenth century the value of land and rents fell and as a consequence many monasteries fell into debt. Some smaller houses merged or, in some cases, closed and most communities, trying to economise, shrank in size. As a result, although there were a few abbeys where significant programmes of innovative building were underway in the fifteenth century, this was not the great age of the monastery. Some abbey churches were modified: the great Cistercian churches at Rievaulx and Fountains, for instance, underwent reordering to take account of their smaller communities, to make room for burials and for nave altars. But most monastic architecture was now driven by a gradual dilution of community life in favour of individual privacy and comfort. This trend was given impetus by the Cistercian Pope, Benedict XII, who authorised half the brothers at a time to eat meat away from the communal refectory. This permanently undermined the sense of community and encouraged individualism and independence. In 1421 Henry V accused senior Benedictines of a life of complacency, luxury and worldliness. To a degree he was right, the rules, once so strictly observed had been weakened and bent and although few monasteries were vice-ridden many were complacent and worldly. Monks had personal property, guest houses and holiday homes and most abbots’ lodgings are rebuilt giving them more privacy and luxury. Possibly the most magnificent, and certainly the best surviving, was the lodging range built by prior Singer at Wenlock Priory, Shropshire in the 1490s. Here the east side of the infirmary courtyard was occupied by a colossal range faced with a grid of windows and buttresses forming the front of a long corridor that gave access to the main rooms. The Prior’s hall, with an elaborate carved wooden roof, dais, fireplace, wall paintings and other luxurious fittings was served by its own private kitchen below. Next door was his private chamber complete with its own gardrobe. It was not only the abbots whose lives became more comfortable; the lives of many individual monks were transformed too. At Durham a new kitchen of great splendour and technical virtuosity was built in 1366-70 to supply the monks with roasted meats which they ate in an agreeable dining room called the Loft where each monk had his own silver cup. The austerity of communal life was relieved by a spectacular new dormitory built in 1398-1404 with individual cubicles each lit by its own low level window while the main room was lit by larger windows above. The seats in the reredorter were partitioned off to give privacy as the monks relieved themselves and in the new cloister openings were glazed and the walks furnished with individual panelled carrals for study. If they should tire of all this Durham owned a rest-house, Finchale Priory, sited in a pretty spot by the river Wear. Here, in groups of four, the brothers of Durham could rest, enjoy themselves and go for country walks. These changes, and others, were accelerated by an improvement in economic conditions in the 1470s, and by the 1520s almost all estates had seen a noticeable rise in income. This boost led to a new wave of monastic construction, most not directed to the liturgical or economic needs of the monastery, but directed to display. Church towers were very popular as were showy gatehouses, guest lodgings and prior’s quarters. Abbot Marmaduke Hoby of Fountains Abbey constructed a colossal bell tower 160ft high with statue niches in the massive corner buttresses. He was not the only one, other northern abbeys at Shap and Furness built similar towers. The tower at Bolton Abbey, begun in 1520, bore an inscription celebrating the abbot who began it. At St. Osyth’s Priory, Essex, Abbot Vintoner built a flashy new gatehouse faced with beautifully ornamented flushwork containing richly carved niches. This was designed to be seen from without, for the other elevation, facing the conventual buildings, was much plainer. I want to move on now from these breathtaking structures that are at the crescendo of gothic architecture in England to a much more mundane issue, but one that is no less important in understanding the fifteenth century. That is brick. The Romans had used brick extensively, and their buildings were ruthlessly plundered for nearly a thousand years. But it was not until the fourteenth century that it started to be manufactured again on any scale. At first it was popular in counties where there was no ready supply of building stone, particularly Norfolk, Suffolk and Kent. It was also convenient in towns like London and Hull where the demand for building materials was particularly high. However in these cases it was normally concealed by rendering or used internally under plaster. It was often also used in vaults where the ribs were of stone and for the hearths and chimneys of fireplaces where its fire resistance was understood. In the fifteenth century brick moved from being a material which met special constructional needs to one of choice. This was mainly due to improvements in manufacture introduced from northern Europe. Makers, many of whom were Flemings, Germans or Dutch, began to produce bricks of a uniform size and colour and could do so in huge quantities relatively cheaply. These craftsmen also knew how to vary the brick colour in the firing and how to make moulded and shaped bricks for decorative effect. These possibilities re-launched brick as a high class building material capable of achieving quite complex architectural effects. In 1414 Henry V agreed to its extensive use at his new palace of Sheen and its associated monasteries and not long afterwards his courtiers followed suit. One of the significant benefits of brick was that it could be made anywhere that had good brickearth. Ideally this would be directly adjacent to the building site thus removing transport costs, one of the most expensive elements in any project. An expert overseer was necessary to identify the earth, particularly to ascertain whether there were suitable iron compounds to achieve a fashionable red colour. After that cheap labour could be used to knead the clay, mould it into bricks, dry them and stack them in either a kiln or a clamp (a pile of dried bricks under which a fire could be stoked). Kilns were permanent and could be re-used, but were smaller. A clamp, such as built at Kirby Muxloe Castle in 1483 fired 100,000 bricks, not an unusually large number. By the early sixteenth century there were hundreds of brick makers in England, some small operators, others contractors working on an industrial scale producing many millions of bricks for a building like Hampton Court palace. At first it was not only the manufactures who came from the continent, for the designers and bricklayers were foreigners too. But soon English masons became proficient in designing and building brick structures and adapted them to English ways of building. All the earliest major brick buildings are associated with the court of Henry VI and include the great Castle at Herstmonceaux, Sussex, begun in c.1441 by Henry’s Treasurer, Sir Roger Fiennes. The streams of design that these early brick buildings contain come together in Henry VI great work of piety at Eton. Eton College was one of the largest and most important religious foundations of the late middle ages established by Henry VI in 1440 to offer prayers for his dynasty and to provide education, ultimately, for 70 scholars. The vision, as it emerged, was on a staggering scale and was never completed, but enough survives of Henry VI’s work to understand what was new about it. This was a college much like William of Wykeham’s New College Oxford, although the vast scale of the chapel proclaimed its primary purpose as a royal chantry. What was new was the comprehensive approach to the use of brick as a high status decorative material including extensive diapering on the principal elevations. Also new was the careful mixture of brick and stone: stone used for the windows, arches and doorways and as a material for string courses and buttresses. A new type of window was extensively used. These were much simpler openings in square heads without any cusping. Such windows appear, at this time in a number of prominent brick buildings. So what was happening at Eton? We know that a large number of the brickmen (as they were called) were foreign and were perhaps employed to create the ambitious diaper patterns. We also know that the king impressed many native brickmen too, many of them from prominent patrons who were themselves constructing large brick houses. Eton College thus became a building in which all the latest ideas about brick construction were used and from which ideas were taken and spread to buildings elsewhere. In some senses Eton became the seminal Tudor structure, the father of a generation of buildings from Hampton Court to the Vyne, Hampshire. Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509. The country over which he ruled was a very different one to that which Henry V had known a century earlier. During the fifteenth century the sense of Englishness that had been developing since the thirteenth century was consolidated. The shift in economic influence from the aristocracy towards the merchants and the gentry created a self-conscious and assertive political community represented in parliament. The Peasants Revolt of 1381 had ensured that this community would not, as in France for instance, make the common people entirely responsible for direct taxation, giving the upper classes fiscal immunity. That all classes shared the burden of taxation meant English society was far less stratified and much more mobile than in most northern European countries. Englishmen now spoke a single language that was rapidly becoming the official language of administration and culture. The invention of printing meant that from the 1480s even relatively poor people could own a book in English and probably 30% of the population could read it. These people were independent and determined and were the people who were now building England. Architecture was no longer just for the Abbot, the Bishop, the Prince and the Aristocrat. It was for the merchant, the gentry, the farmers and the artisan. While Rome had been the inspiration for building in England from 410 until 1300, and God had been the inspiration after that, it was now the independently minded Englishman represented I think best by Robin Hood. Of course nobody knew in 1509 that in only thirty years the whole infrastructure of everyday life was to be blown away by the Reformation. This remarkable little island with a strong independent culture, populated with buildings of originality and beauty, with a flourishing religious life and a wealthy and influential middle class was to fundamentally change. So were its buildings, cut off from streams of thought on the mainland. But this is the story of my next lecture. You will have to wait until October 10th to hear about it though! In the meantime have a great summer and I hope that you will take the chance to visit some of the amazing buildings that I have discussed in the last year.

Mistral-7b-Instruct Response

Ladies and Gentlemen, I'm glad you could join me today as we delve deeper into the fascinating world of English architecture during the late Middle Ages and early Tudor period. In our previous discussions, we've explored how economic crisis and demographic changes shaped the architectural landscape, focusing mainly on the perspectives of the wealthy and powerful. Today, I'd like to take a different approach and shine a light on the living conditions of ordinary people, the unsung heroes of this period. Let's begin by recalling the devastating impact of the Black Death, which struck England in the mid-14th century, decimating entire communities and leaving vast swathes of land depopulated. This terrible scourge led to numerous socioeconomic changes, some of which yielded surprising benefits for the survivors, in terms of both living standards and economic opportunities. One such benefit was a reversal of land management trends among the nobility. Landowners, who formerly relied on labor-intensive agriculture to maximize their income, increasingly chose to lease their lands to tenants in return for a steady rent. This shift paved the way for the emergence of a new class of tenant farmers, who profoundly influenced the architectural landscape, particularly in the countryside. These new tenant farmers could now afford to construct timber-framed farmhouses that reflected their newfound economic security. Characterized by their intricate, exposed wooden frames and filled in with infill materials like clay or wattle, these homes showcased regional variations while promoting greater thermal comfort and economy. For instance, Suffolk-style farmhouses feature tall, jettied gables, while in Norfolk, the farmhouses boast lower, steeply pitched roofs. One notable example is the Alton Priors Farmhouse, situated in Wiltshire, which has survived to the present day. As these social and architectural landscapes adapted, so did the residences of the wealthy. For instance, there was a declining tendency to move residences, resulting in an increased need for storage and more local consumption of goods. This shift consequently led to architectural innovations among the rich, who aspired to emulate the convenience and comforts found in the homes of the newly affluent tenant farmers. Another architectural trend among the aristocracy was the construction of towers and gatehouses, which symbolized high status. These structures served as statements of power, reflecting the social stratification of the era. For example, the towers in Hedingham Castle, Essex, date back to the 15th century and are adorned with elaborate decorative schemes, demonstrating the prestige of the castle's inhabitants. Over time, these structures evolved to become more integrated with domestic spaces as a means to provide privacy and security. Meanwhile, commercial architecture, in the form of inns, taverns, and alehouses, flourished. These establishments served various functions within the community, providing travelers with shelter and sustenance, catering to local social engagements, and fostering a thriving commerce scene. For example, The King's Head Inn in Letheringsett, Norfolk, is a well-preserved example of a medieval inn, which still welcomes guests seeking a taste of history. Architecturally, these establishments could be distinguished from one another by factors like exterior décor and room configurations. The late 15th and early 16th centuries saw significant developments in church architecture as well. With royal patronage playing an essential role, numerous ecclesiastical constructions were completed, including Gothic Revival structures and magnificent abbeys. For instance, the 15th-century Chapel of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey exemplifies the refined craftsmanship and decorative detailing of the period. However, monastic architecture also underwent notable changes, as monks and abbots seeking individual comfort and privacy prompted the introduction of architectural innovations within their communities. For example, the Great Cloister at Glastonbury Abbey, built in the late 15th century, featured private living cells and secluded gardens, ensuring a more personal, accommodating environment for its inhabitants. The 15th century was marked by a shift from a rigidly stratified society to one that was more mobile, leading to numerous socioeconomic changes that had far-reaching implications for architecture. As we venture further into this era, we'll witness breathtaking architectural creations that anticipate the groundbreaking transformations of the Reformation. In the meantime, I invite you all to explore these architectural marvels firsthand, for there's no substitute for experiencing history in the flesh.

I-ORPO Response

Good afternoon, everyone. I'm glad you could join us today for another lecture on architecture. As we continue our exploration of the relationship between socioeconomic change and architectural styles and practices, I'd like to shift focus today. In our previous discussion, we spent a great deal of time talking about how economic crisis and demographic changes affected the architecture of the late Middle Ages. It's time now to turn our attention to the living conditions of ordinary people during that period. Before we begin, I'd like to remind everyone that we are tracing the thread of English architectural history from the late Middle Ages, through the early Tudor period, to the late Elizabethan period. We won't be able to cover every aspect of the history of architecture in England during this time, but I'll do my best to provide an overview of the main trends and changes—and a few juicy examples along the way. Today, we'll examine an interesting period when it comes to the architectural landscape of England. The 14th and 15th centuries saw the rise of a new class of tenants, the reversal of land management trends, and the emergence of a new consumer class. At the same time, timber-framed farmhouses, residences of the rich, and commercial architecture all underwent drastic changes. Before we dive into those specific developments, let's first discuss the Black Death, the agricultural recession that followed, and how they helped create a more prosperous society for the survivors, which had far-reaching impacts on architecture. The Black Death, which hit Europe in the mid-14th century, was a plague that devastated the entire continent, killing about 50 million people or almost one half of the entire European population. When it arrived in England, towns and cities were emptied as citizens fled to try to escape the pestilence. When everyone else had died out, the few survivors who remained suddenly had access to a plethora of empty buildings, open spaces, and underused land. Rents immediately rose as farmers who had previously been tenants and then fled, found that landlords had no alternative than to give them better deals. This not only resulted in an agricultural recession but also gave wealthy landowners a great opportunity to increase their income. Although landlords lost a great deal of their capital to the plague in the short term, they ultimately benefited from the increase of the wealth of their tenants—and the reversal of land management trends that followed. Today, you might think that the Black Death would have a pretty significant impact on the architecture of the time, but it turned out to have quite the opposite problem. Since people found they had a lot of building materials just lying around, construction really slowed down. People would take the plentiful wood from vacant houses, for example, and use it to build themselves new homes right away. But by the later decades of the 14th century, the plentiful resources had mostly been used up, and new architecture began to emerge. As a result of the demographic shift mentioned above, we saw a lot of new agricultural practices being employed during the later medieval period. Farmers began to use fertilizers like lime and ash, which dramatically increased soil productivity. Farmers also began to adopt new farming methods such as rotating crops and letting pasture land lie fallow after harvest. The success of these practices brought about a great increase in per-acre production and made farming a whole lot more profitable in the 15th century. And what did wealthy tenants do with all that abundance? Well, they built. At the beginning of the 15th century, tenant farmers who had inherited land suddenly found themselves with a lot of wealth. Although it took some time for these farmers to amass these resources, the trend continued throughout the 15th century. The most prosperous of them built for themselves large houses on their own land—these houses were often timber-framed, but they varied widely by region. In the East Anglian counties and much of Essex, for example, wealthy tenant farmers built rectangular houses, often with thatched roofs, featuring central chimneys. In the Midlands, wealthy tenant farmers would often build central-aisled halls, surrounded by open-fronted galleries, and other features that might surprise you. In the West of England, timber-framed farmhouses would often feature steeply pitched roofs, overhanging galleries, and large chimneys that rose from each end. As for Northern houses, they could rarely be called ""timber-framed""—instead, they were predominantly mud and stone constructions. So—why was all this happening? Well, to put it plainly, these wealthy people had become consumers. Their sudden wealth gave them a new interest in display and an appreciation for comfort. The galleries that surrounded their houses, for instance, served both a practical and an aesthetic purpose—they were a way of displaying the social status of the occupant and also served to bring more light into the house. The central chimney allowed better use of floor space and the ability to keep the house warmer, and the pitched roofs created a taller interior space. So, what about the houses of the rich? Well, although people had been building timber-framed structures during the early 14th century, they still tended to be very flexible—they could be easily dismantled by the occupants and transported to the next location if necessary. By the later 14th century, however, the practice of dismantling houses changed—nobility and wealthier peasants began to build permanent houses. As with their humbler counterparts, the houses of the rich also tended to be rectangular in shape, although they often featured larger galleries and more extensive timber framing. They could also feature two halls, one for secular life and one for religious life, but as I explained earlier, galleries began to be added to the exterior. This not only provided additional display space for social status and allowed more light into the house but also created a separation between the areas for secular and religious life, which I'll discuss later. There was another change that we began to see in the 14th century, as well. The houses of the rich began to shift from a focus on display of social status to the display of personal comfort. In the early 14th century, houses would often be built without much thought to the occupants' comfort levels; this began to change. Instead of rooms in the house being devoted to specific uses, such as the great hall and the kitchen, there was now more emphasis on personal comfort—more emphasis on the needs of the occupant as an individual. But although there is evidence that a few houses had been built with private bedrooms as early as the 13th century, most houses didn't have them. Towards the end of the 14th century, however, the architectural trend changed dramatically. Private bedrooms became a more common feature in new houses for the wealthy. There was a need for privacy, it seems, but how exactly did that private bedroom come into fashion? Well, there are a couple of possibilities. On the one hand, the nobles and wealthier peasants might have seen an increase in status by adopting this new architectural practice. On the other hand, the new private bedroom might have come about because people decided that having more privacy within the house was a better use of space, and this was the best way in which to achieve it. Whichever the case, the new private bedrooms were a perfect example of the trend towards a greater emphasis on the needs of the individual. By the middle of the 15th century, there were two reasons for the shift in housing plans: first, people had a greater awareness of the need for personal comfort, and second, there was a new appreciation of privacy. Now, let's talk about a bit of an interesting topic: commercial architecture. In the 14th century, taverns, alehouses, and inns all began to proliferate. They each served different purposes in different areas, and for that reason, they each had different architectural styles. Taverns, for example, generally served a more upmarket clientele. Although there wasn't a clear distinction between taverns and alehouses, it's worth noting that taverns had the higher status of the two. Inns served a more middle-class clientele—mostly travelers and the like. As for alehouses, they tended to serve a less upmarket clientele, as well as being less refined in their architecture. Inns would have stables, haylofts, and other facilities associated with travelers. Innkeepers often built large houses right next to the stables to give them security, warmth, and to provide a clear demarcation between the parts of the building used by travelers and the innkeeper. Many of these inns also had their own breweries, which provided their main source of income. Alehouses, on the other hand, had a more limited number of facilities and tended to only serve the local clientele. Many of these tended to be single-storied, with small rooms on the upper floor serving as bedrooms. Now, you might wonder when it is that the innkeepers started to build houses for themselves. Did they only do it to make themselves more comfortable? The first houses built for innkeepers were rather austere—they were rectangular, built of timber, thatched, with one or two galleries, and often no private rooms. There was also not much of a separation between private rooms and areas for drinking or sleeping, or work areas. It was only in the 14th and 15th centuries that innkeepers began to build more comfortable, private homes for themselves. These homes typically had their own separate kitchens and dining areas, as well as a hall. However, the innkeepers often did not have their main living quarters directly above the tavern or inn—usually, they resided in a separate bedroom, located on the upper floor. It was only in the 15th and 16th centuries that more elaborate structures began to be built, such as a chamber over the central hall, as well as new kitchens and other rooms. So why did everyone want a separate hall, kitchen, and bedrooms? I think part of the answer lies in the change I talked about before—people began to prioritize the comfort of the individual, and these new features represented a way in which they could achieve that. But the need for more display space was also evident in the development of the inn. After all, the inn itself was now used as a space for public consumption (food and drink), but private rooms for sleeping and eating were a status symbol. So, what about church architecture? Well, as we've seen with other types of architecture, church architecture also saw changes in the late 14th and 15th centuries. And we're already familiar with some of the features of churches built around that time, such as the timber-framed roofs, tiled floors, and the addition of galleries to the chancel or nave. But did these developments also have an impact on church architecture? Well, the first thing we should mention is that royal patronage began to have a significant impact on many architectural projects from the late 15th and early 16th centuries. And the same was true for churches. Edward III, for instance, founded the Guild of the Holy Trinity in 1336, which became an important center for patronage. King Henry VII, at the beginning of the 17th century, founded the College of Arms, which, in turn, became an important patron; he also founded the College of Heralds, which played an important role in promoting architectural construction. Many scholars believe that the wealth of medieval churches came from the benefactions of the church. As we know, Henry VII was also a wealthy landowner, who amassed vast amounts of wealth for his time. Although it's not entirely clear, some historians argue that this money from wealthy landowners might have come from the benefactions to the church as a whole. We can see the growth of patronage reflected in buildings like Dean’s Yard, the college of the dean and canon at Westminster Abbey, and the royal chapels and their attached palaces—these, of course, were all in the London area. In addition to church architecture, we can also see evidence for new styles in the later, large churches as well, such as those built in the Cotswold area. The main difference between the early and the late churches was the architecture and planning. Early churches were more likely to be rectangular in shape and built entirely of stone, with little decoration beyond stone carvings and carvings of saints. But by the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th, architects began experimenting with new styles, which is something we'll hear more about as we continue the series. One of the most interesting differences between the late medieval and early Tudor periods was the change in monasticism. As the wealth of the church grew and as people's interests in the past grew, so did their interest in monasticism. By the end of the 15th century, England had more than 900 monastic houses, including abbeys, monasteries, and convents. Although each of these houses varied in size and appearance, they tended to have the same basic organizational structure. The houses would be organized around a single quadrangle, which would house the main conventual buildings as well as the church. At the center of this quadrangle was the church itself, while the monks lived in rooms and halls that surrounded it. There would also be a library, where scholars of monasticism would spend their time. There might also be auxiliary buildings, such as bakehouses, breweries, and mills, which would provide the necessities of life. In early 16th-century monasteries, there would often be another wing built in the manner of a late medieval palace, including a hall, kitchen, and other rooms that we've been discussing. At this point, most of the monasteries had the basic structure of a monastic community, with a few additional buildings. As wealth increased, however, there was a shift towards personal comfort, and monastic communities were no exception. As we've seen, one of the reasons for this shift was the fact that the monasteries themselves had become places of comfort for people. Before, monastic communities had been places of work, where monks lived simply and devoted their lives to prayer. During the 14th and 15th centuries, however, monastic communities became much more comfortable. And although personal comfort would not have been a priority for the monks themselves, they might have had their own private chambers for privacy and personal reasons. As the wealth of the churches increased, so did the wealth of the monasteries. However, monastic communities were still subject to the same economic pressures that other sorts of communities were. Many wealthy monks began to have private bedrooms, even as the number of people in the monastery began to dwindle. And as the monasteries grew wealthier, they began to have many more private rooms which were often more lavish in appearance. The living quarters of the abbots themselves became much more luxurious than they had been in the past. By the beginning of the Tudor era, we can see evidence of great changes in the architecture of the churches: more private rooms, more comfort, and a shift towards a much more personal approach to architecture. So, how did the rise of brick contribute to architectural advances? Well, brick was really only beginning to be used in the later 15th and early 16th centuries, and it had several important advantages over timber. First, brick is more fireproof—it burns more slowly and more easily than wood, so it's much harder to light on fire in the first place. It's also much easier to work with, unlike timber, which is a relatively soft material. It's also a material that could be used to build almost anything—you could build a house, a church, or a castle out of brick. In addition to providing more protection from fire, brick is also a material that can handle greater stress and strain—it's a much harder material than wood. And as people became more interested in architecture, the availability of brick meant that they could choose a more durable and longer-lasting material—a material that would last throughout the entirety of the building project. The first improvements to brick production in England came from the northern European countries in the later 15th century, and this had a significant impact on the aesthetics of architecture from the late medieval period through to the Elizabethan period. Brick was so effective in improving safety in buildings that many architects began to experiment with different patterns for buildings. In addition to the more classical Gothic style that we've been discussing, architects began to experiment with a variety of styles that would eventually become known as Tudor architecture—which we are familiar with today. Bricks were used in a variety of different patterns in many buildings, and they had no particular name back then. By the late 15th and early 16th centuries, however, brick had become a staple of English architecture. In buildings like Eton College, the roofs were made out of brick, and the walls were made of brick in a diagonal arrangement that allowed the walls to be self-supporting. These buildings were known as ""clinchered walls"" or paneled walls, and they provided a great deal of the strength needed to create the very stable and secure structures necessary for the Tudor period. As we come to a close, there are a few larger social and cultural shifts that took place between the late medieval and early Tudor period that are important to keep in mind. Although the Black Death had a huge impact on architecture overall, this period was characterized by a number of very distinctive social and economic changes. After the Black Death ravaged Europe, there was a great reduction in feudalism and serfdom. This was partly caused by the increase in population and the decrease in farmland, but it was also caused by the shift from feudalism to capitalism. This was the time when people began to own more land and had a greater sense of freedom—these changes, of course, were not limited to England, but they were certainly important in the overall development of the country. The period between the late medieval and early Tudor periods was also characterized by rising literacy, and people became more interested in science, medicine, and technology in general—all of which would eventually lead to the Renaissance. In general, the rise of capitalism during this time created a more mobile and less stratified society, which would eventually come to an end with the Reformation. This period was also a time when merchants, merchants' wives, and merchants' daughters grew in prominence—people who we tend to think of as ""buxom,"" as they had more opportunities to spend their money in ways they had previously not been able to. This growing consumer class created a big shift in the economy and in architecture, as people became more interested in owning goods, which meant that fewer people needed to be able to afford food. This shift also meant that people spent more time working and had less time for leisure activities. With an increasing number of books in circulation, people also became more literate, and literacy was closely related to wealth—if you were rich, it was important to be able to read and write. People wanted to be able to spend their money on books, and so book production began to flourish. This led to a greater emphasis on craftsmanship, on education, and on a greater appreciation of beauty. And although we tend to think of this period as being less beautiful than the Renaissance that would follow, people during this period valued beauty in a very different way. As we come to a close, I'd like to give you a few things to think about before we continue our lectures on architecture. We've talked quite a bit about the social and economic changes that were driving architectural trends during the Tudor period—what did these developments mean for the architectural practice of the time? What were the implications of a less stratified society, of a more mobile society, of a more capitalistic society, and of other changes going on at the time? What impact did these changes have on architecture more generally, and what are some examples that come to mind when you think of this time period? What did people value in architecture during this time period? What kinds of architectural trends were taking place? And how can we best understand these trends and the changes that were taking place during this time? These are just a few of the things I'm curious about, and I look forward to hearing your thoughts as we come to a close today. Thank you for joining me for another lecture on architecture, and I'll see you again next week for more on the history of architecture.

SFT Response